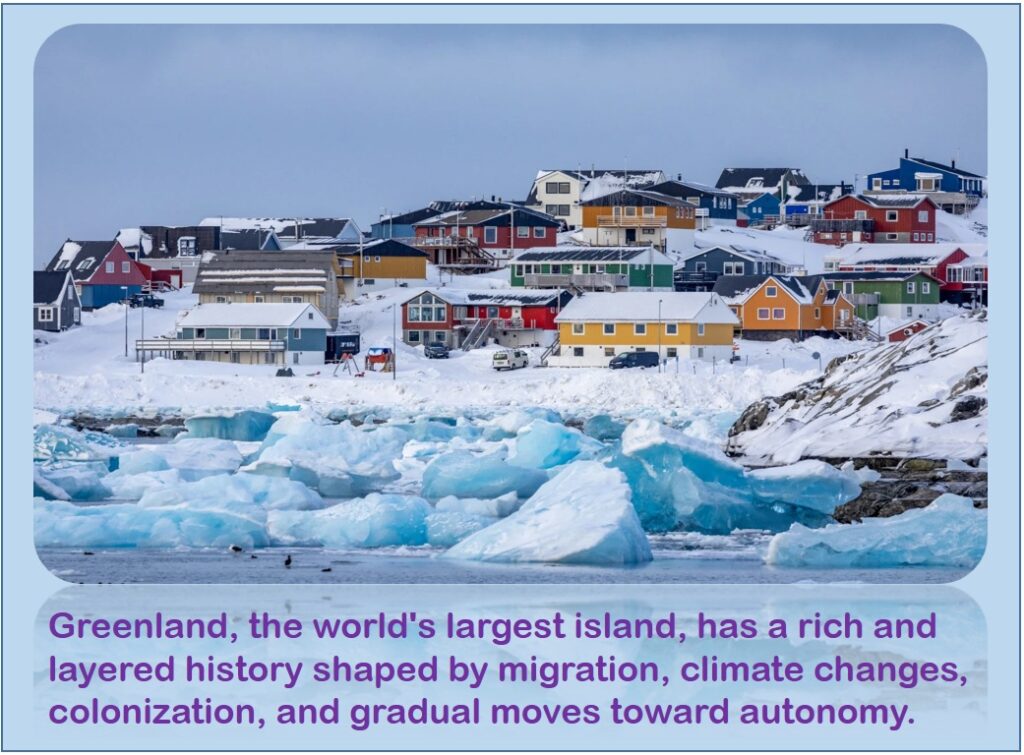

History of Greenland

Greenland History Facts: The world’s largest island, has a rich and layered history shaped by migration, climate changes, colonization, and gradual moves toward autonomy. Its story spans thousands of years, from prehistoric human settlements to modern political developments.

Prehistoric and Early Inhabitants

The first humans arrived in Greenland around 2500 BCE, migrating from northern Canada across the frozen Arctic. These early Paleo-Inuit groups, part of the Independence I culture, spread along the northern coastline, relying on hunting marine mammals and adapting to the harsh Arctic environment. Over the millennia, several waves of migration occurred, with at least six distinct Inuit cultures arriving at various times. The ancestors of the modern Greenlandic Inuit, part of the Thule culture, migrated around 1200 CE from northern Canada via the Nares Strait. These groups thrived in the icy conditions, developing sophisticated hunting techniques and social structures that allowed them to survive the Little Ice Age, a period of cooling that began in the 13th century.

Norse Settlement and the Viking Period

In 982 CE, the Norwegian explorer Erik the Red, banished from Iceland for manslaughter, arrived in Greenland and named it “Greenland” to attract settlers, despite its largely icy terrain. He returned in 986 CE with colonists, establishing two main Norse settlements: the Eastern Settlement near present-day Qaqortoq and the Western Settlement near Nuuk. These communities grew to a population of 3,000–6,000 across about 280 farms, supported by a relatively warmer climate that allowed for agriculture and trade with Europe. Christianity was introduced in the 11th century by Erik’s son, Leif Eriksson, after his return from Norway, and a bishopric was established in 1126.

Interactions between the Norse and the expanding Inuit Thule culture began in the 13th century. However, the Norse settlements declined in the 14th century and vanished by the 15th century. Theories for their disappearance include climate cooling during the Little Ice Age, which made farming unsustainable; soil erosion from overgrazing; conflicts with Inuit groups; isolation from Europe due to reduced trade; and possible disease or emigration back to Iceland or Norway. After this, Inuit became the island’s sole inhabitants for centuries.

European Rediscovery and Colonization

Following the Norse disappearance, European expeditions from England and Norway visited Greenland in the 16th and 17th centuries, but sustained contact came with whalers in the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1721, Danish-Norwegian missionary Hans Egede arrived near present-day Nuuk, establishing a trading company and Lutheran mission, marking the start of modern colonial rule. Greenland became a Danish colony after the separation of Denmark and Norway in 1814.

Denmark maintained a trade monopoly until 1950, gradually exposing Greenlanders to the outside world while protecting them from exploitation. During World War II, with Denmark occupied by Germany in 1940, the United States provided protection and established military bases, including Thule Air Base (now Pituffik Space Base). Greenland was returned to Danish control in 1945.

Post-War Integration and Autonomy

After the war, Denmark addressed Greenlandic grievances by abolishing the trade monopoly in 1951 and integrating Greenland as a full part of the Kingdom of Denmark in 1953, ending its colonial status. Reforms improved the economy, transportation, and education. In 1979, Greenland achieved home rule, granting self-governance in areas like education, health, and fisheries. The 2009 Self-Government Act further expanded autonomy, transferring most powers except defense, foreign policy, and currency to local authorities, following a 2008 referendum approved by 75.5% of voters. This act allows Greenland to pursue full independence through a future referendum, though economic challenges have delayed it.

Present Status of Greenland (as of 2026)

Greenland remains an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, the largest of Denmark’s three constituent parts by area. It is geographically part of North America but politically and culturally tied to Europe. Covering 2.16 million square kilometers (836,000 square miles), about 80% is ice-covered, restricting habitation to coastal areas.

Population and Demographics

As of late 2025, Greenland’s population is approximately 56,831, with projections of a 20% decline by 2050 due to emigration and low birth rates. Around 89.5% are Greenlandic Inuit, 7.5% Danish, and the rest other Nordic or foreign nationals. The capital, Nuuk, has about 19,600 residents. Travel between towns relies on boats, helicopters, and planes, as there are no roads connecting settlements. No individual owns land; it is communally managed.

Economy

The economy is heavily dependent on fishing and seafood exports, which account for over 90% of physical exports. Other sectors include mining (rare earth minerals), tourism, sealing, whaling, and hunting. GDP growth was 0.8% in 2025, expected to remain modest at 0.8% in 2026, down from 2% in 2022, signaling stagnation. Denmark provides an annual block grant of about 4.3 billion Danish kroner ($610 million), covering roughly half the budget. Challenges include a shrinking workforce, reliance on imports, and vulnerability to climate change, which is melting ice and opening new resource opportunities but also threatening traditional livelihoods. Per capita GDP is around €25,000 (2006 figures, adjusted for inflation).

Politics and Governance

Greenland operates as a devolved parliamentary democracy within Denmark’s unitary constitutional monarchy. The head of government is Jens-Frederik Nielsen (since April 2025). It has its own parliament (Inatsisartut) and government (Naalakkersuisut), handling internal affairs like education, health, justice, and taxation. Defense and foreign policy remain with Denmark, though Greenland influences Arctic matters. No military of its own; the U.S. maintains Pituffik Space Base under a 1951 agreement.

Independence is a long-term goal for many; polls show 56% favor it, but 45% oppose if it lowers living standards. Recent U.S. pressure has highlighted tensions, with some opposition parties suggesting direct talks with Washington, bypassing Copenhagen. In April 2025, reports emerged of U.S. disinformation campaigns undermining Danish ties.

U.S. President’s Statements on Greenland

As of January 2026, U.S. President Donald Trump (47th President, serving since January 20, 2025) has aggressively pursued acquiring Greenland, reviving interest from his first term (2017–2021). He frames it as a national security priority to counter Russian and Chinese influence in the Arctic, citing Greenland’s strategic location, rare earth minerals, and military potential.

Key statements include:

- In 2019 (first term), Trump called it “essentially a large real estate deal.”

- In March 2025, he said the U.S. would “go as far as we have to go.”

- On January 6, 2026, the White House stated Trump is discussing “a range of options,” including military force, as it’s “always an option at the commander-in-chief’s disposal.”

- On January 9, 2026, Trump declared: “We are going to do something on Greenland whether they like it or not. Because if we don’t do it, Russia or China will take over Greenland, and we’re not going to have Russia or China as a neighbor.”

- He added: “I would like to make a deal, the easy way. But if we don’t do it the easy way, we’re going to do it the hard way.”

- Trump has linked it to NATO, claiming without him, “you wouldn’t have a NATO right now,” and suggesting it might force a choice between the alliance and Greenland.

U.S. officials, including Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, have echoed this, with Hegseth confirming Pentagon contingency plans. Diplomacy is preferred, but force remains threatened.

International Responses to U.S. Interest

Responses have been overwhelmingly negative, emphasizing Greenland’s sovereignty and warning of NATO’s potential collapse. Polls show 85% of Greenlanders oppose U.S. annexation.

Greenland’s Response

Greenlandic leaders assert “Greenland is not for sale” and “we don’t want to be Americans.” On January 10, 2026, all five political parties issued a joint statement rejecting Trump’s threats, stressing self-determination and opposition to becoming part of the U.S. Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen called U.S. rhetoric “disrespectful” and linked to fantasies of annexation. Some opposition figures suggest direct negotiations with the U.S., reflecting frustrations with Denmark.

Denmark’s Response

Denmark views it as a threat to its territorial integrity. Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen warned on January 5, 2026, that a U.S. attack would end NATO and “everything,” including post-WWII security. She urged Trump to stop threats against an ally and emphasized Greenland’s right to decide its future. Denmark seeks talks but faces domestic debate on clinging to Greenland amid independence desires.

European and NATO Allies’ Responses

A joint statement on January 6, 2026, from leaders of the UK, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, and Denmark affirmed: “Greenland belongs to its people, and only Denmark and Greenland can decide on matters concerning their relations.” They stressed collective NATO action on Arctic security and non-negotiable sovereignty. French President Emmanuel Macron denounced the “law of the strongest,” questioning if it could lead to invasions elsewhere. European leaders initially held back public criticism but now rally behind Denmark, viewing U.S. actions as a NATO crisis that could undermine alliances. U.S. Vice President JD Vance criticized Denmark for not securing Greenland adequately.

Broader International Views

China has noted U.S. efforts as tone-setting and testing Europe but hasn’t directly intervened. Analysts warn military action would be “absurd” and counterproductive, straining global ties. U.S. domestic polls show opposition to force, and even Republicans express concerns. Talks between U.S., Danish, and Greenlandic officials are ongoing, with Rubio planning meetings.

Also Read: